‘Academic publishers: The original enshittificationists’

Matt Wall on Medium, applying Cory Doctorow’s theory of enshittification to scholarly publishers:

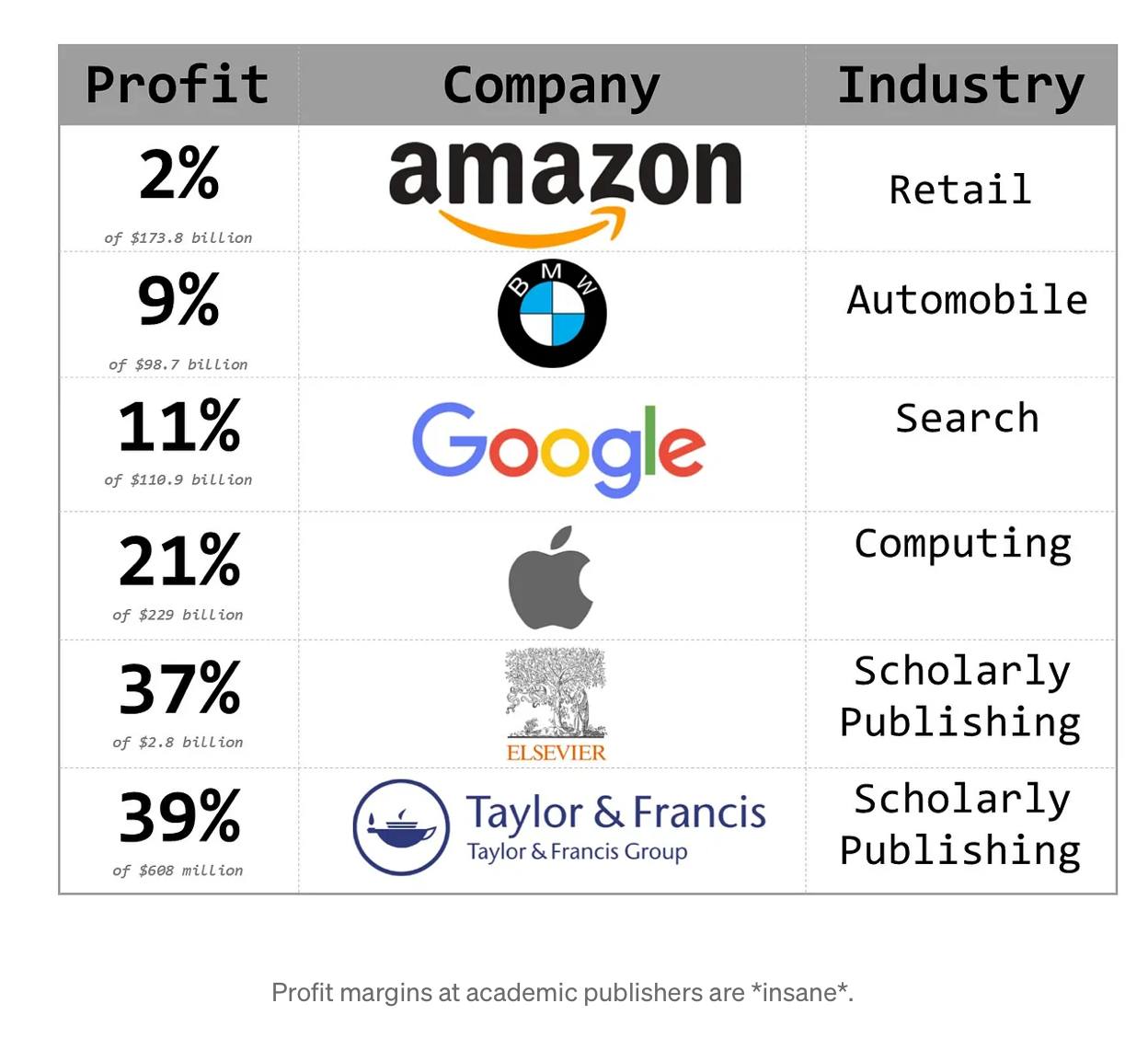

Here’s the thing though, the final part of Doctorow’s enshittification process as applied to online platforms is “then they die”. There currently seems to be little evidence of that. The outright profiteering and blatant exploitation of researchers has arguably shifted up a gear in the last couple of decades with the advent of open-access fees, but this process has been going on since the 1970s; academic publishers are the original enshittificationists (enshittifiers?). They have kept on re-inventing ways of enshittifying the process of disseminating scholarly information and maintaining their grossly-inflated profit margins, most notably by co-opting the open-access movement and using it as an excuse to charge ridiculous publication fees. They are a leech on the body of scholarly work, slowly sucking out the life-blood, but just never quite enough that researchers and institutions abandon them wholesale. My feeling is that they will continue doing so for many decades into the future.

‘Quantifying Consolidation in the Scholarly Journals Market’

I missed this David Crotty post from the fall, on still-more concentration in scholarly publishing:

Overall, the market has significantly consolidated since 2000 — when the top 5 publishers held 39% of the market of articles to 2022 where they control 61% of it. Looking at larger sets of publishers makes the consolidation even more extreme, as the top 10 largest publishers went from 47% of the market in 2000 to 75% in 2023, and the top 20 largest publishers from 54% to controlling 83% of the corpus.

It’s a good, transparent post—complete with spreadsheet shared for scrutiny. The consolidation figures are indeed staggering—and more reason still to wrest back publishing control from the oligopolist firms.

My beef with the post is the way it’s used as a cOAlition S battering ram.

These data show two main waves of market consolidation. The first wave aligns with the rise of The Big Deal journal subscription package model, roughly 2000 to 2006. […] From 2006 through 2018, there was only minor movement toward consolidation. […] The next wave of market consolidation began in 2018 and continues through the present day, presumably driven by the rise of OA due to new funder regulations.

Emphasis added, since that’s a big “presumably.” Yes, it’s probably true that Plan S, until its recent reversal, helped bring on some consolidation, in a case of disastrous unintended consequences. But it’s a profound stretch to lay the “second wave” of publisher consolidation—given a trend-line that, since the early 1970s, has shown a fairly consistent slope—on cOAlition S alone. Correlation, etc.

P.S.: I thought publisher consolidation was supposed to be a good thing.

From 2022: ‘Reflections on guest editing a Frontiers journal’

Serge Horbach, Michael Ochsner, and Wolfgang Kaltenbrunner, in a Leiden Madtrics post, detail a vexing guest-editing role at a Frontiers journal, circa late 2022:

Reviewers are selected by an internal artificial intelligence algorithm on the basis of keywords automatically attributed by the algorithm based on the content of the submitted manuscript and matched with a database of potential reviewers, a technique somewhat similar to the one used for reviewer databases of other big publishers. While the importance of the keywords for the match can be manually adjusted, the fit between submissions and the actually required domain expertise to review them is often less than perfect. This would not be a problem were the process of contacting reviewers fully under the control of the editors. Yet the numerous potential reviewers are contacted by means of a preformulated email in a quasi-automated fashion, apparently under the assumption that many of them will reject anyway. We find this to be problematic because it ultimately erodes the willingness of academics to donate their time for unpaid but absolutely vital community service. In addition, in some cases it resulted in reviewers being assigned to papers in our Research Topic that we believed were not qualified to perform reviews. Significant amounts of emailing and back-and-forth with managing editors and Frontiers staff were required to bypass this system, retract review invitations and instead focus only on the reviewers we actually wanted to contact.

Their post appeared just one month before ChatGPT’s public roll-out. How many AI peer-review “solutions” like this are in the works now?

‘Towards Robust Training Data Transparency’

As if on cue, Open Future releases a new brief call for meaningful training data transparency:

Transparency of the data used to train AI models is a prerequisite for understanding how these models work. It is crucial for improving accountability in AI development and can strengthen people’s ability to exercise their fundamental rights. Yet, opacity in training data is often used to protect AI-developing companies from scrutiny and competition, affecting both copyright holders and anyone else trying to get a better understanding of how these models function.

The brief invokes core, Mertonian science norms in its argument to put muscle behind Europe’s AI Act:

The current situation highlights the need for a more robust and enabled ecosystem to study and investigate AI systems and critical components used to train them, such as data, and underscores the importance of policies that allow researchers the freedom to conduct scientific research. These policies must include a requirement that AI providers be transparent about the data used to train models […] as it will allow researchers to critically evaluate the implications and limitations of AI development, identify potential biases or discriminatory patterns in the data, and reduce the risk of harm to individuals and society by encouraging provider accountability.

‘AI Act fails to set meaningful dataset transparency standards for open source AI’

Open Future’s Alek Tarkowski, writing in March about Europe’s AI Act:

Overall, the AI Act does not introduce meaningful obligations for training data transparency, despite the fact that they are crucial to the socially responsible development of what the Act defines as general purpose AI systems.

Tarkowski’s post is nuanced, and well worth a read. My mind kept drifting to the scholarly-publishing case—in which scholars’ tracked behavior, citation networks, and full-text works might train propriety models built by the likes of Elsevier. As Tarkowski hints here—echoing Open Future’s July 2023 position paper—open science norms around data sharing should be brought to bear on legislation and regulation. The case for FAIR-like principles to apply to models trained on scholarly data is stronger still.

‘Publishers can’t be blamed for clinging to the golden goose’

I missed this Steven Harnad piece from last May. It is trademark Harnad:

So, you should ask, with online publishing costs near zero, and quality control provided gratis by peer reviewers, what could possibly explain, let alone justify, levying a fee on S&S [scientists and scholars] authors trying to publish their give-away articles to report their give-away findings? The answer is not as complicated as you may be imagining, but the answer is shocking: the culprits are not the publishers but the S&S authors, their institutions and their funders! The publishers are just businessmen trying to make a buck. […] Under mounting ‘open access’ pressure from S&S authors, institutional libraries, research funders and activists, the publishers made the obvious business decision: ‘You want open access for all users? Let the authors, their institutions or their research funders pay us for publication in advance, and you’ve got it!’

Harnad, the original (and wittiest) advocate for the “green” repository route, is basically right. It’s not just scholars, of course—we’re not free agents when it comes, say, to productivity metrics imposed by university managers. But the academic system as a whole (funders included) is responsible for letting the oligopolist publishers laugh, as Harnad has it, all the way to the bank.

Jeff Pooley is affiliated professor of media & communication at Muhlenberg College, lecturer at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania, director of mediastudies.press, and fellow at Knowledge Futures.

pooley@muhlenberg.edu | jeff.pooley@asc.upenn.edu

press@mediastudies.press | jeff@knowledgefutures.org

CV

Publications

@jpooley@scholar.social

Orcid

Humanities Commons

Google Scholar

Projects

mediastudies.press

A non-profit, scholar-led publisher of open-access books and journals in the media studies fields

Director

History of Media Studies

An open access, refereed academic journal

Founding co-editor

History of Social Science

A refereed academic journal published by the University of Pennsylvania Press

Founding co-editor

Knowledge Futures

Consulting, PubPub, an open source scholarly publishing platform from Knowledge Futures, the scholarly infrastructure nonprofit

Fellow

Annenberg School for Communication Library Archives

Archives consulting, Communication Scholars Oral History Project, and History of Communication Research Bibliography

Consultant

MediArXiv

The open archive for media, film, & communication studies

Founding co-coordinator